On their journey to the Jombolok Volcano Field in the Eastern Sayan Mountains of Buryatia in the summer of 1851 the Atkinsons decided to visit a remarkable mine run by a remarkable Frenchman – Jean Pierre Alibert. Lucy describes the visit to the Batagol Mine, the ruins of which still lie in the mountains to the east of the town of Orlik, thus:

“From this place we visited a lead mine belonging to a Frenchman. On the road to it we passed many Bouriat winter dwellings, sheltered in a pretty well-wooded valley, with a broad and rapid stream running through it. These people differ from the Kirghis in having fixed abodes. They are exceedingly aristocratic, possessing both summer and winter dwellings. Farther on we found them in their summer habitations, surrounded by numbers of horses and cattle, but few sheep. The men are more industrious than the Kirghis, though not so gentlemanly-looking; whereas the women, some of them, were really pretty, which is probably owing to their not being so hard worked.

“To reach Mr. Alibere’s mine we had a mountain to ascend from the valley of the Oka, which led us into a region of lakes, near which the road was very bad, caused by the deep morass, where we were floundering about in mud and water at every step we took. Unpleasant though it was, we had crossed worse places; and we rather astonished our host when we told him so. Once arrived, we found everything we could desire except cleanliness, and this it was impossible to have, the black lead penetrating everything. Our host had wisely built a bath, a very necessary precaution. He has a farm some ten versts distant, so that his table was supplied with butter, cream, and vegetables, fresh daily; this was more than we expected to find, I never thought to have even a potato.

“From this mountain, which is dome-shaped, I saw what to me was a wonderful sight, and the effect of which was beautiful, viz. a rainbow beneath, not above us; I never saw such a thing before, nor have I seen it since.

“We had some difficulty with Alatau over the morass, so resolved to invest a little money in the purchase of a pair of reindeer from a Samoiyede family, the only one said to be existing in these regions. They live in tents like the Tartars, conical and covered with skin; their dress also consists of skins. However, we found it a useless investment. The saddle was continually getting twisted, and I learned from our men that it required great tact for even a grown person to sit comfortably. So after the first day’s riding, we were obliged to abandon the use of them, and seat the boy on a horse, where he rode very comfortably. The delays in arranging his saddle on the reindeer impeded our progress greatly. He was obliged to be strapped on his horse; and it was rather fatiguing for him to be seated so many hours as he sometimes was. When sleep overtook him, we were obliged to carry him, which we did in turns.”

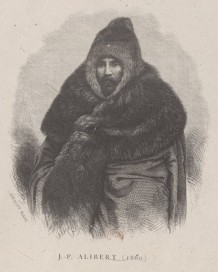

Alibert had arrived in the Sayan Mountains in 1847. He had been prospecting for gold in a river near Irkutsk when he came across lumps of graphite in his pan and decided to follow the stream to find the source, which turned out to be more than 300kms away in the Sayan Mountains. At that time, high quality graphite for use in lead pencils was in short supply, the important mine in Borrowdale, Cumbria, having closed down. Despite the remoteness of this location, Albert realised he could turn a profit by mining the mineral and therefore set about building workings on top of a hill at a place called Batagol.

When the Atkinson’s visited it was still being developed, but by the mid-1850s production was beginning in earnest. Alibert struck an exclusive deal with the German pencil maker Faber and managed to export his graphite on the backs of reindeers – still found in the area – and then down the rivers to the Pacific coast, where it was loaded onto ships bound for Europe. The mine became the main source of graphite for the world and Alibert was later awarded numerous medals and honours across Europe. Pencils made from Alibert’s graphite by Faber became the standard.

In the extract above Lucy mentions a reindeer they tried to use to carry Alatau, but found it too difficult. Today these deer are still herded by the local Soyot people – Lucy called them Samoyeds – a distinct ethnic minority, about 3500 of whom live in the region. They are very similar in culture to the neighbouring Tuvans and until recently still lived part of the year in birch-bark ‘chums’ – conical structures similar to native North American wig-wams. They also spoke a Turkic language similar to the Tuvans, but this has largely disappeared, although some attempts are being made to revive it. I now realise that our local guides to Jombolok were Soyots, almost all of whom are believers in shamanism.

The Batagol Mine continued to produce very high-quality graphite until it closed in the 1950s, although it is still remembered locally, as is Monsieur Alibert, who had a reputation for treating his workers very well. During our trip we passed within a few miles of the mine, but it was not until I returned to England that I was able to find out more about it. You can watch a slide-show here about a trip to visit the site of the mine made almost a decade ago:

Reblogged this on Bernard Grua | Regards sur le monde.

LikeLike