It has always been a mystery to me why Thomas and Lucy Atkinson should have been so comprehensively forgotten by history. Most people in Britain have never heard of them and those that have would probably struggle to explain their extraordinary achievements as explorers.

Part of this can be explained by Victorian morality, which would have judged Thomas’ bigamous marriage to Lucy particularly harshly. Part is also due to the fact that, unlike others, Thomas was not a ‘scientific’ explorer ie he did not keep meticulous scientific notebooks, nor record or map his exact routes. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that he did collect geological and archaeological specimens – possibly also plant specimens too – but he certainly lacked the scientific training and map-making skills of some of his contemporaries.

Typical of the criticism levelled against Thomas is this statement from the Dictionary of National Biography, which is often repeated whenever Atkinson’s name is brought up. Referring to his second book, Travels in the Regions of the Upper and Lower Amoor (1860), his entry states:

“The latter work was highly praised by The Athenaeum on its publication, but its authenticity was subsequently questioned. Doubts were raised whether Atkinson had personally travelled on the Amur, and the book was shown (The Athenaeum, 9 Sept 1899) to be at least in part a plagiarism of Richard Maak’s work Journey to the Amur (Puteshestvia na Amur), published in St Petersburg in 1859.”

Let us be clear about this. Despite its title, it is undeniable that Thomas did not travel on the Amur River – although he was able to visit some of its headwaters in the Khinghan Mountains in Mongolia. This was not because he did not want to make the dangerous journey. He tried very hard to get permission, but was repeatedly turned down by the Russian authorities. On 1st October 1850, for example, he wrote from Irkutsk in Eastern Siberia to Lord Bloomfield, the British Ambassador in St Petersburg, asking him to request that Tsar Alexander II should extend the terms of his passport to allow him to travel as far east as the Kamchatka peninsula. “Should I be successful in obtaining His Imperial Majesty’s permission to continue my journey I shall then bring back views of the whole of these mountain regions from Kokan (today’s Kokand-ed) to Kamchatka”, he wrote.

On 19th January 1851, having received no reply, he wrote a second letter to Lord Bloomfield repeating his request that he should intercede with the Tsar for permission to travel: “I am now exceedingly anxious about it, as the season will soon arrive when I must decide what shall be my plans for the summer and take advantage of the winter roads to perform parts of my journey.”

Alas, on the recommendation of the governor of Eastern Siberia, General Nikolai Muravyev-Amursky, his request was turned down. Tensions between Britain and Imperial Russia were increasing and with British forces already in China, it is likely that the Governor thought Atkinson might be spying out the land with a view to a British invasion of the mouth of the Amur and northern Manchuria. In fact, this is precisely what happened – with little success – during the Crimean War, which started in 1854.

Without the permission he sought, it was impossible for Thomas to travel further east. He was not even allowed to visit the famous mines at Nerchinsk to the east of Lake Baikal, but instead decided to strike out into the completely unexplored regions to the north and west of Irkutsk, where he made some wonderful discoveries, including the now-famous Jombolok volcano field.

So why did he name his book Travels in the Regions of the Upper and Lower Amoor? Let’s go back to 1859-60, when he was writing it. Already by this time his health was fading. Lucy says as much in letters she wrote to Thomas’ old friend and mentor, the Reverend Charles Spencer Stanhope. He was, as ever, short of money and desperate to complete and obtain payment for this second book. I believe he originally wanted to publish both his Siberian books as a double-volume set, but that his publishers, not sure if it would be a success, only agreed on the first volume, which appeared in 1858 as Oriental and Western Siberia. After its huge success they were very happy to publish a second book, but wanted to take advantage of the increasing interest in the Amur River and so pushed Thomas to slant it towards concentrating on the Amur.

The problem was that most of his manuscript was not about the Amur at all, but further material on Central Asia, particularly on Thomas and Lucy’s stay in Kapal in present-day eastern Kazakhstan. My guess is that most of this had already been written and was left over from the time the first book was published two years before. There are clues in the cover of the Amur book; if you look, you will see it is elaborately embossed with a scene that took place in Kapal, when Thomas was almost killed by a runaway sleigh. Kapal is several thousand kilometres away from the Amur River.

Inside, we will find that after a few introductory chapters on the deserts of Central Asia, from page 116 to 353 the book is about Eastern Kazakhstan. There follows a chapter about caravan routes in Central Asia (26 pages). Only on page 380 does Atkinson begin to write about the Amur region. The following five chapters, totalling a mere 119 pages, in contrast to the rest of his writing, which is in the first person, are third-person descriptions of the Amur region. These are followed by another 50-odd pages of lists of flora and fauna of the Amur region.

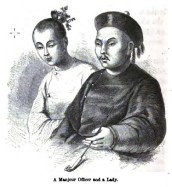

So less than a third of the book is about the Amur. A dozen or so of the illustrations – mostly portraits – in these last few chapters certainly come straight from Travel on the Amur River made by order of the Siberian Department of the Emperor’s Russian Geographical Society in 1855, Richard Maak’s famous work on the Amur, which was published in 1859.

In fact, these portraits in Thomas’ book, showing different ethnic groups settled along the Amur, are all contained on a single page of Maak’s book, as you can see below. However, I do not think it is reasonable to say this was plagiarism. In the Preface to Thomas’ Amur book, dated July 1860, he makes it clear that he has used material from Russian sources: “I am indebted to several of the Russian officers who were employed in the great expedition into Manjouria for facilities in acquiring information during my travels and I beg them and numerous Asiatic friends, to whom I am under similar obligations, to accept my grateful thanks.” Having himself been refused permission to join the great expedition down to the Amur, it must have been somewhat galling for Thomas to see Maak’s book.

He goes on: “With regard to the illustrations, it is here necessary to state that to the numerous landscape series, engraved from my own drawings, I have added a few characteristic portraits, copies from a work recently published by the Russian government.” This was clearly a reference to Maak’s book and a look at the illustrations proves this point.

Illustrations from Maak’s book as used by Thomas Atkinson

The fact that Tsar Alexander II sent Thomas an emerald and diamond ring following publication of his Amur book suggests that there was no bad feeling in Russia about Thomas using some of the illustrations and general descriptions contained in Maak’s book.

So at least part of the reason why Thomas and Lucy eventually faded from public consciousness may have been because of ill-founded allegations about plagiarism, combined with Victorian sensibilities about divorce. Jealousy by rivals may well have been another reason. I will come back to this subject in a future posting.

One thought on “Refuting the charge of plagiarism”